![]()

![]()

Office of E-Government and IT Office of Management and Budget

Version 0.7 December 3, 2009

Powered by the Federal Chief Information Officers Council

Table of Contents

1.2. Supporting Transparency, Participation, and Collaboration

1.3. Value Proposition to the Public

1.4. Value Proposition to Agencies

2. Data.gov Operational Overview

2.1. Functionality of Data.gov Website

2.2. Determining Fitness for Use and Facilitating Discovery

2.3. Current Data Sets Published via Data.gov

2.4. Who Makes Data.gov Work: Key Partnerships

3. Future Conceptual Solution Architecture

3.1. Security, Privacy and Personally Identifiable Information

3.4. Data Infrastructure Tools

3.5. Agency Publishing Mechanisms

3.6. Incorporating the Semantic Web

3.7. Working with Other Government Websites

4.1. Expose Additional Datasets via Data.gov

4.2. Ensure Compliance with Existing Requirements

4.3. Evolve Agency Efforts based on Public Feedback

4.4. Sign-Up and Complete Data.gov Training

4.5. Participate in Data.gov Working Groups

4.6. Evaluate and Enhance Policies and Procedures

4.7. Initiate Pilots for Semantic.Data.gov

6. Appendix A – Detailed Metrics for Measuring Success

Table of Tables

Table 1: Core Users of Data.gov

Table 2: Datasets and Tools by Agency/Organization (as of 11/18/09)

Table 3: Agency Participation Metrics

Table 4: Overall Performance of Data.gov Metrics

Table of Figures

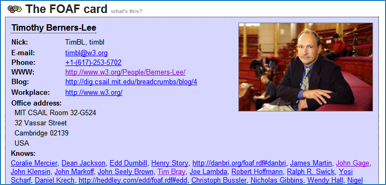

Figure 1: Third Party Participatory Site

Figure 2: Third Party Disasters Map Mash Up and Collaboration Example

Figure 3: Current (November 2009) State and Local Data Dissemination Sites

Figure 4: DOI (USGS) Featured Tool Panel Example

Figure 6: Data.gov Tools Catalog

Figure 7: Data.gov Metadata Page

Figure 8: Conceptual Architecture Overview Diagram

Figure 10: Catalog Record Architecture

Figure 11: Developer Architecture

Figure 12: Search Integration Architecture

Figure 13 : Notional Data.gov Search Page User Interface

Figure 14: Notional Data.gov Search Results User Interface

Figure 15: Notional Data.gov Geospatial Search Tool

Figure 16: Publishing Architecture

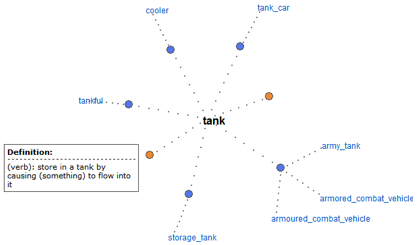

Figure 17: Visualization of Wordnet Synonym Set for "tank"

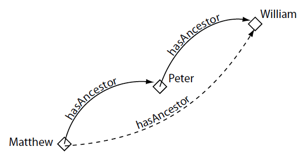

Figure 19: Transitive Genealogical Relationship

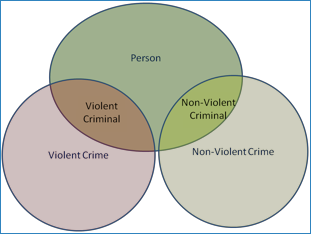

Figure 20: Using Set Theory to Model Violent Criminals

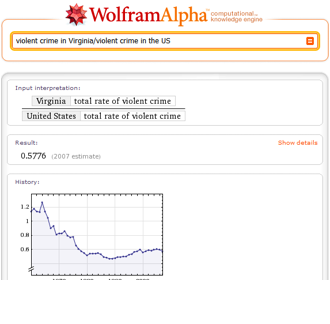

Figure 21: Computing Results from Curated Data

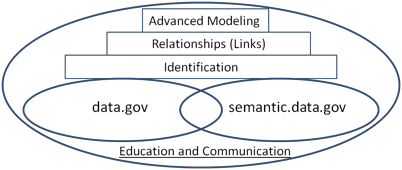

Figure 22: Semantic Evolution of Data.gov

1. Data.gov Strategic Intent

Data.gov is a flagship Administration initiative intended to allow the public to easily find, access, understand, and use data that are generated by the Federal government.

Data.gov operates at two levels. The website is the public presence, delivering on the government’s commitment to transparency. On the policy level, Data.gov is about increasing access to data that agencies already make available and making available additional data sources that have not been freely presented to the public in the past.

For data that are already available, the emphasis is improved search and discovery as well as provisioning of data in more usable formats. For data that have not been widely available due to current business processes and policies, the focus is on providing data in a more timely and granular manner while still protecting privacy, confidentiality, and security.

On an operational level, Data.gov’s focus has been on creating the website and associated architecture designed to catalog Federal datasets, improve search capabilities, and publish information designed to allow the end user to determine the fitness for use of a given dataset for a particular application. The goal is to create an environment that fosters accountability and innovation. Realizing the vision for the website requires agencies to:

· Make their most relevant and informative data and related presentation tools available through Data.gov;

· Do so in a manner that supports use and innovation by stakeholders – public or private; and

· Agree on a shared performance management framework centering on quantifying the value of dissemination of high quality, secure, public information that does not raise privacy or confidentiality concerns.

The purpose of this document is to lay out the overall strategic intent, operational overview (“as is”), future conceptual architecture (“to be”), and agency next steps. This document is intended to help organize and transform government operations and guide technology development.

The Department of the Interior’s and the Environmental Protection Agency’s Chief Information Officers (CIOs) serve as the co-leads for development and operations of the Data.gov website, with support provided by the General Services Administration and the Office of Management and Budget. This team worked with many agency points of contact to launch Data.gov on May 21, 2009. The Data.gov launch underlined the President’s commitment to open and transparent government.

The emphasis on access is not new; many agencies already have in place successful approaches. However, the launch of the Data.gov website continues, reinforces, and focuses efforts at the US government (enterprise wide) level. This focus is consistent with implementation of OMB’s M-06-02 Memorandum titled “Improving Public Access to and Dissemination of Government Information and Using the Federal Enterprise Architecture Data Reference Model”[1]. Specifically, OMB Memorandum M-06-02 requires agencies to “organize and categorize [agency] information intended for public access” and “make [data] searchable across agencies”. Data.gov is a major mechanism by which agencies can fulfill requirements in OMB Memorandum M-06-02 in a more consistent and citizen friendly way.

The launch of Data.gov has catalyzed similar initiatives across the United States and indeed internationally. In addition to focusing at the enterprise level, Data.gov envisions guidelines and mechanisms that facilitate coordination and sharing of best practices across these similar initiatives.

1.1. Data.gov Principles

A vibrant democracy depends on straightforward access to high quality data and tools. Data.gov’s vision is to provide improved public access to high quality government data and tools. OMB Circular A-130 states that “the free flow of information between the government and the public is essential to a democratic society”. Data.gov will provide developers, researchers, businesses, and the general public with authoritative Federal data that are actively managed by data stewards in a framework that allows easy discovery and access.

Key Data.gov principles include:

1. Focus on Access

Data.gov is designed to increase access to government data as close to the authoritative source as possible. The goal is to strengthen our democratic institutions through a transparent, collaborative and participatory platform while fostering development of innovative applications (e.g. visualizations, mash-ups) and analysis by third parties.

Policy analysts, researchers, application developers, non-profit organizations, entrepreneurs and the general public should have numerous resources for accessing, understanding and using the vast array of government datasets.

2. Open Platform

Data.gov will use a modular architecture with application programming interfaces (API) to facilitate shared services for agencies and enable the development of third party tools. The architecture, APIs, and services will evolve based on public and agency input.

3. Disaggregation of Data

Data should be disaggregated from agency reports, tools or visualizations to enable direct access to the underlying data.

4. Grow and Improve through User Feedback

Feedback should be used to identify and characterize high value data sets, set priorities for integration of new and existing data sets and agency provided applications, and drive priorities and plans to improve the usability of disseminated data and applications.

5. Program Responsibility

Agency program executives and data stewards are responsible for ensuring information quality, providing context and meaning for data, protecting privacy and assuring information security.

Agencies are also responsible for establishing effective data and information management, dissemination, and sharing policies, processes and activities consistent with Federal polices and guidelines.

6. Rapid Integration

Agencies should rapidly integrate current and new data into Data.gov with sufficient documentation to allow the public to determine fitness for use in the targeted context.

7. Embrace, Scale and Drive Best Practices

Data.gov will implement, enhance and propagate best practices for data and information management, sharing and dissemination across agencies, with our state, local and tribal partners as well as internationally.

1.2. Supporting Transparency, Participation, and Collaboration

The Data.gov vision and principles are made real through a focus on transparency, participation, and collaboration.

Transparency

At the core of Data.gov is the intent to make Federal sector data more accessible and usable. Increasing the ability of the public to discover, understand, and use the vast stores of government data increases government accountability and unlocks additional economic and social value. Dissemination of public domain data has always been an integral mission activity. Data.gov takes this traditional activity to the next step by providing coordinated and cohesive cross-agency access to data and tools via a non-agency specific delivery channel.

Data.gov will develop to increasingly enhance the ability for developers, researchers, businesses, and the general public to find information by offering metadata catalogs integrated across agencies, and will eventually provide the opportunity for agencies to leverage Data.gov shared data storage services if they so desire. A more consolidated source for data and tool discovery allows the public to navigate the Federal sector data holdings without having to know, in advance, how Federal agencies and data programs are organized.

Furthermore, Data.gov is working with USASearch.gov to develop search capabilities that will enhance the public’s ability to find data, tools, and related Federal web pages from an integrated search. These capabilities can also increase transparency by enhancing the discoverability of specific data and information from the tools made available through Data.gov[2]. Such accessibility also addresses one additional goal of Data.gov, to enhance the ability of Federal agencies to more easily discover information available from other agencies for common mission purposes.

Participation

Public participation is a key pillar of the open government agenda and is critical to the success of Data.gov. The site provides mechanisms for the public to participate and the evolution of the site will greatly benefit from public participation (i.e., suggestions). Future versions of the site are proposed to include the ability of the public to transparently post their suggestions for data and rate and rank their priorities. Data.gov increases the opportunity for the public to discover and understand the data resources available and, for those with the inclination, to subsequently build applications, conduct analyses, and perform research. A basic value proposition of Data.gov is to spur additional analysis and innovation.

The Administration is particularly interested in developing ways for the public to become more engaged in the governance of our Nation. To facilitate this enabling, the public can analyze issues from their own perspective with the data they have paid for with their tax dollars. Data.gov seeks to engage the public in expanding the creative use of Federal data beyond the walls of government by encouraging the development of innovative ideas (e.g., web applications); combining Federal and other data to gain new insight into efficiency and effectiveness of government; pursuing new economic and socially-based ventures; and thereby enriching the lives of citizens.

Figure 1: Third Party Participatory Site[3]

For example, USAspending provides transparency into agency spending. But the underlying data are made available for use by others, resulting in several third party sites. Figure 1 highlights such a site.

Thought is being given to how Data.gov might evolve to become compatible with the semantic web or data web. Such a future would involve the adoption of protocols, and their implementation by agencies, to encode meaning into data in such a way that they are directly interpretable by computers, so that instead of having “data on the web”, there will be a “web of interoperable data”. Through the data web, data aggregation and analysis might be done directly through machine interaction, and new applications and services might be more efficiently created.

The Federal government has a wealth of information; if made more available in accessible formats, there is the potential to spur an explosion of innovation. As such, Data.gov places a strong emphasis on the dissemination of public information generated by the Federal government in platform-independent, standards-based formats that promote creative analysis – via data that are authoritative and granular.

Collaboration

Key collaboration mechanisms to improve and evolve Data.gov include direct feedback, comments, and recommendations from the public. For example, individuals are encouraged to suggest datasets to add to Data.gov, rate and comment on the value and quality of current datasets, and suggest ways to improve the site overall.

Figure 2: Third Party Disasters Map Mash Up and Collaboration Example[4]

1.3. Value Proposition to the Public

An important value proposition of Data.gov is that it allows members of the public to leverage Federal data for robust discovery of information, knowledge and innovation.

Making Federal data more transparent has many benefits including the potential to maximize the return on investments in collecting and managing the data themselves by transcending agency stovepipes, encouraging data to be disseminated in reusable and interoperable formats, and facilitating enhanced search abilities. As was the case for the Human Genome project, releasing datasets beyond the walls of government allows for expanded public access, facilitating creativity and ingenuity.

Understanding the potential value of Data.gov rests with considering the nature and quantity of the Federal data themselves. For example, Performance and Accountability Reports[5] (PAR) are currently published by agencies in a document-centric report. While PAR is of value to students of government performance, the reports are not standardized and for the most part the underlying data is programmatically inaccessible – making it difficult and effort intensive to do additional analysis on the provided information, much less look at cross-agency trends and performance. In the future the standard reports, such as the PAR, could separate and publish via Data.gov the underlying data. This vision of unbundling the finished report from the underlying data, and potentially augmenting or replacing the traditional document-centric report with data visualizations or web applications, can be extended across many other classes of Government reports.

Further, many opportunities exist for adding value such as exploring more timely release of in-process data assets, rather than accumulating, processing, and disseminating data on longer, agency-centric timelines. In particular, more timely release of data would support more timely, third-party analysis and have the potential to empower more proactive public-initiated dialog.

An example of another value proposition is an application that Forbes created from data available from a variety of Federal and external sources to develop their list of America’s safest cities. From their website is a description of the data and how they use it:

“To determine our list of America's safest cities, we looked at the country's 40 largest metropolitan statistical areas across four categories of danger. We considered 2008 workplace death rates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2008 traffic death rates from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; and natural disaster risk, using rankings from green living site SustainLane.com. It devised its rankings by collecting historical data on hurricanes, major flooding, catastrophic hail, tornado super-outbreaks, and earthquakes from government agencies including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the United States Geological Survey, the Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and private outfit Risk Management Solutions. We also looked at violent crime rates from the FBI's 2008 uniform crime report. The violent crime category is composed of four offenses: murder and non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery and aggravated assault. In cases where the FBI report included incomplete data on a given metro area, we used estimates from Sperling's Best Places.”

The concept of delivering government data to the public from a single catalog was popularized by the District of Columbia with its data catalog available at http://data.octo.dc.gov/. The District provides citizens with access to 405 datasets from multiple agencies, and the public can subscribe to live data feeds or access data in a variety of formats.

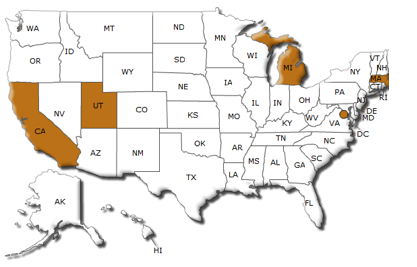

The public sector data catalog concept went national with the launch of Data.gov. Since the launch of Data.gov, many state and local governments have launched their own data catalog sites to better share public sector data. The map shown below has the States highlighted where new Data.gov-inspired catalog websites have been launched. In addition, several cities such as New York and San Francisco have launched Data.gov-inspired websites. In addition, several countries such as New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom have launched or are in process to launch sites inspired by or similar to Data.gov.

Figure 3: Current (November 2009) State and Local Data Dissemination Sites

End Users of Data.gov

The user community for Data.gov spans multiple groups including data enthusiasts, technical developers, visualization experts, oversight organizations, researchers, academics, businesses, media, mission advocates, application developers, public sector employees, and individuals interested in knowledge discovery, as indicated in Table 1. Access modes are both direct and indirect. Direct access is discovering and using the data directly from Data.gov and agency web sites. Indirect access happens when the public accesses third-party applications, visualizations, or data infrastructure tools that in turn access Federal data via application programming interfaces (APIs) or bulk download of data sets.

The user communities are all encouraged to continue providing direct and indirect feedback to Data.gov. Direct feedback takes the form of emails, comments, and ratings posted through the website. Indirect feedback includes blog postings, tweets, magazine articles, conference panel discussions, and both traditional and new approaches to engaging in the Data.gov “conversation”.

|

Core Users |

Use |

Avenues for Interaction |

|

General Public |

The general public can use the platform to download datasets. The general public can also discover and access Federal data via third-party visualizations, applications, tools or data infrastructure. |

Website, Tools (Agency-Provided and Third Party) |

|

Application Developers |

Application developers can develop and deliver applications by leveraging the raw data, APIs or other methods of data delivery. |

APIs, Third-Party Data Infrastructure |

|

Government Mission Owners |

Mission owners can expand access to and leverage data from their public sector partners to enhance service delivery, drive performance outcomes and effectively manage government resources. |

Website, Tools (Agency-Endorsed) |

|

Data Infrastructure Developers |

Data infrastructure developers can increase the utility of Data.gov by enhancing its search capability, metadata catalog processes, data interoperability and ongoing evolution. |

APIs |

|

Research Community |

The research community can help unlock the value of multiple datasets by providing insight on a plethora of research topics. |

Website, APIs |

|

Data Infrastructure Innovators |

Existing entities and new ventures developing innovative data and application offerings that combine public sector data with their own data. |

Website, APIs, Bulk Downloads |

Table 1: Core Users of Data.gov [6]

1.4. Value Proposition to Agencies

Since

most agencies have information dissemination as part of their mission, Data.gov

is a key component for improved mission delivery. It is a delivery channel to

enable agencies to make their data more accessible, discoverable,

comprehensible, and usable. As such, agencies may choose to use Data.gov as

their primary means of information dissemination to the public and forego the

need to maintain their current processes for publishing their data.

Specifically, agencies can use Data.gov not only to store their metadata via

the Data.gov metadata storage shared service, but agencies can also forego

management of their own data storage infrastructure by leveraging what will

become the data storage shared service described in Chapter 3.

Since

most agencies have information dissemination as part of their mission, Data.gov

is a key component for improved mission delivery. It is a delivery channel to

enable agencies to make their data more accessible, discoverable,

comprehensible, and usable. As such, agencies may choose to use Data.gov as

their primary means of information dissemination to the public and forego the

need to maintain their current processes for publishing their data.

Specifically, agencies can use Data.gov not only to store their metadata via

the Data.gov metadata storage shared service, but agencies can also forego

management of their own data storage infrastructure by leveraging what will

become the data storage shared service described in Chapter 3.

As additional data and tools are made available through Data.gov and as improvements are made to metadata and data quality, and search, discovery, and access tools, it will become an important resource to user groups, leading in turn to greater the visibility and use of data. By this logic, the benefit to participating agencies increases as additional agencies begin to participate more actively. In this manner, agencies have a vested interested in not only their own active participation, but the active participation of their peer agencies.

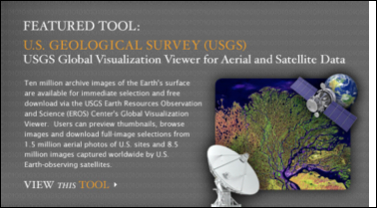

From an individual agency perspective, one value proposition of Data.gov is that it gives high visibility to data that the agency wants to share with the public. As illustrated by an example in Figure 4, Data.gov includes revolving panels of “featured tools and datasets” that provide even more visibility and showcase high-quality data and tools provided by the Federal government. These featured tools and datasets are rotated on a regular basis to keep the content fresh and representative of the many topical areas within the purview of the Federal government.

Data.gov assists agencies with their information dissemination requirements. It also provides agencies with a new and important public feedback mechanism. As Data.gov continues to evolve, agencies will be provided with new and more robust ways to obtain feedback directly from the end users of their authoritative data. For instance, the public can provide specific narrative feedback on published data and tools.

Figure 4: DOI (USGS) Featured Tool Panel Example

Agencies that actively participate in Data.gov not only share their data more widely, but also increase the public’s awareness of their works in key mission areas. Active participation in Data.gov increases overall visibility and can engender a greater trust and appreciation for agency missions, their roles, and their overall performance in the service of the country. Transparency of agency data provides the public with the ability -- either through government tools, third-party web applications, or other means -- to understand their government, its impact on their lives, and hold it accountable. This transparency can also translate into the discovery and implementation of collaborative initiatives with other Federal organizations.

1.5. Measuring Success

Data.gov will measure its success based upon primary and secondary metrics. The three primary metrics are: (1) cross agency participation, (2) use of disseminated data, and (3) the usability of the data available through Data.gov. All primary metrics will be recorded over time and displayed on the performance dashboard tool discussed in Chapter 3, Future Conceptual Solution Architecture. The initial secondary performance metrics are many and are included in “Appendix A – Detailed Metrics for Measuring Success”.

Data availability, data usage and data usability are keys to successful implementation:

1. Data Availability

Agency participation will be evaluated based upon the quantity of data that they make available through Data.gov, relative to the total amount of data that the agency has eligible for such access (i.e., the release of which does not compromise privacy, confidentiality, security or other policy concerns).

Agencies should prioritize information dissemination efforts to accelerate dissemination of high value data sets in accord with mission imperatives, agency strategy, and public demand.

2. Data Usage

Usage metrics include the number of Data.gov page views, downloads of data, API calls, success in facilitating innovation as demonstrated through the number and scope of third party applications, feedback from users and intra-governmental collaboration on Data.gov-related content.

Success in facilitating innovation could be measured through proxies including the diversity of use of Data.gov’s content and Data.gov’s propagation. Diversity of use will be ranked by the average number of datasets used by externally produced applications or tools, and the number of registered and active third-party applications. User feedback metrics could measure the volume and sentiment of feedback, both overall and on a dataset basis.

3. Data Usability

Usability will be measured by how clearly and completely the strengths and weaknesses of agency data are conveyed through identification and descriptive information, and technical documentation. This will be measured via completeness of the structured data provided and maintained by agencies that represent integrated datasets in the Data.gov platform. Additional metrics include: how detailed are the key words that feed the search; the degree to which semantic web approaches as described in Chapter 3 are used; and user data set scoring.

2. Data.gov Operational Overview

2.1. Functionality of Data.gov Website

The Data.gov website utilizes a three-tiered design. The first tier features a home page which offers navigation to the catalogs, initial user feedback options, a vehicle for featuring datasets and tools, and site use tutorials. The choice of featured datasets and tools are replaced periodically, illustrating the datasets that support different missions throughout the government. The home page is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Data.gov Home Page

The second tier of the Data.gov website currently incorporates three catalogs:

1. "Raw" Data Catalog[7]: Features instant view/download of platform-independent, machine readable data in a variety of formats.

2. Tool Catalog: Provides the public with simple, application-driven access to Federal data with hyperlinks. This catalog features widgets and data-mining and extraction tools, applications, and other services.

3. Geodata Catalog: Includes trusted, authoritative, Federal geospatial data. This catalog includes datasets and tools. This catalog employs a separate search mechanism.

Note that there is overlap among these three catalogs. For instance, there are some geospatial data in the “raw” data catalog and the Geodata Catalog technically contains both “raw” data and tools.

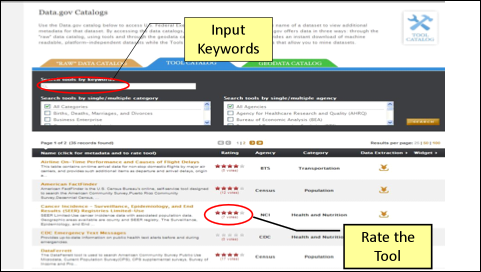

The Tools Catalog and its features are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Data.gov Tools Catalog

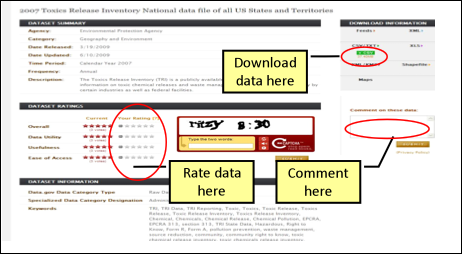

The third tier of the Data.gov website displays the information necessary for the data user to determine the fitness of the dataset for a given use. The source of that information is the metadata template completed for each dataset by the contributing agency. Note that the end user will see the core metadata and the metadata associated with the domain specific metadata standards (e.g. geospatial, statistics) where those exist. This third tier view and features are shown in Figure 7. The end user will access this page for links to download the data/tools and descriptions, as well as links to the source agency. Also on this page, the end user will be able to download the data and/or tools, rate the data, and even comment on the data or tool.

Figure 7: Data.gov Metadata Page

2.2. Determining Fitness for Use and Facilitating Discovery

The term “metadata” means an external description of a data resource. The term is often used to describe information that enables: (1) discovery of data, (2) understanding the provenance and quality of the data, or/and (3) analysis of the data via a set of machine readable instructions that describe the data and its relationships, as might be required by a data web

The Data.gov website uses a metadata template as a means of describing the core attributes of each dataset and data extraction/mining tools cataloged. The information in the metadata template both powers the search engine and provides access to information about the potential utility of the dataset for a given use.

The Data.gov metadata template currently includes descriptive information about the context of the data collection, the study design, dataset completeness, and other factors that might influence a data analyst’s determination regarding the utility of the data for a specific purpose. The core elements in the Data.gov metadata template were based on the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, Version 1.1 standard.

Given the use of the metadata template for populating the search database and providing context information about the available data sets, the most critical elements of the metadata template include the data descriptions, keywords, data sources, and URLs for technical documentation. Agencies should think both broadly and specifically when selecting key words – the robustness of the text-based search capability will drive the extent to which users can find the data in which they are interested. An inter-agency committee of metadata and search experts will continue to refine the Data.gov metadata template as both the vision and architecture of the site evolve.

Domain specific communities within the Federal government are encouraged to develop their own supplemental metadata standards that would be harmonized with the core metadata specification and co-exist in a federated context. For instance, in addition to the core elements defined for datasets and tools, the Data.gov metadata template currently accommodates additional metadata elements for datasets that are classified as “statistical”. On the other hand, for communities that already have their data assets cataloged using a standard metadata format, APIs can be built to ‘mine’ that metadata for the elements needed to populate its metadata template. Such is the case for the geospatial datasets incorporated from the Geospatial One Stop (GOS) (geoData.gov). The Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC) Content Standard for Geospatial Metadata (FGDC-STD-001-1998) is required by and used to catalog the data in GOS. To enable incorporation into Data.gov of all data and tools published through GOS that meet the Data.gov data policy, an application has been developed that allows population of the Data.gov metadata template directly from the FGDC record that currently resides in GOS. GOS-published data exposed via the Data.gov Geodata Catalog thus feature both the standard Data.gov metadata, as well as the full FGDC content standard maintained in GOS.

With regard to geospatial datasets, Data.gov also provides access to specialized data extraction tools (e.g., USGS Global Visualization Viewer) providing datasets in specific image data file formats such as satellite imagery and aerial photographs. These imagery data include additional metadata that describe relevant information about the data such as the spectral content, geospatial coordinates, image data quality (e.g., cloud cover), and other relevant attributes.

2.3. Current Data Sets Published via Data.gov

The Data.gov initiative was established by the Federal Chief Information Officers’ Council and the E-Government and Information Technology Office at the Office of Management and Budget. A March 11, 2009, memorandum requested that Federal Chief Information Officers (CIOs) provide information on their agency datasets that would potentially be suitable for the Data.gov initiative. This initial data call yielded 76 data sets and tools from 11 agencies.

Data.gov was launched on May 21, 2009, to serve as the single access point for publicly available authoritative Federal data. As part of the initial launch, a sequence of data calls went to Executive Branch agencies soliciting nominations for agency datasets that were already being disseminated to the public. The initial goal of Data.gov was to publish data characterized by minimal risk and high value to potential end users.

Since the initial launch, over 110,000 individual data resources are accessible through Data.gov. These data resources include structured data and tools for the public to visualize and use data. Additional datasets continue to be added through the Data.gov dataset submission process. On July 3, 2009 Data.gov added a “Geospatial” catalog that houses both structured data and tools. Table 4 details the November 18, 2009, view of datasets and tools on Data.gov from each participating agency/organization. Note that some “tools” counted in Table 4 actually represent hundreds, thousands, or millions of datasets. For instance, the Department of the Interior’s US Geological Survey has a tool on Data.gov called “USGS Global Visualization Viewer for Aerial and Satellite Data”. This tool alone represents ten million archive images of the Earth's surface.

In the future, Data.gov will include more visible reporting of agency/organization participation. This reporting will be published in pre-determined intervals, and performance metrics will also be integrated into the performance dashboard referenced in Chapter 3 and made available via APIs.

|

Agency |

Entries in Raw Data Catalog |

Entries in Tool* Catalog |

Entries in Geospatial Catalog |

Total |

|

Department of Agriculture |

0 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Department of Commerce |

17 |

30 |

108,137 |

108,184 |

|

Department of Defense |

0 |

194 |

0 |

194 |

|

Department of Education |

0 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

|

Department of Energy |

6 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

62 |

25 |

0 |

87 |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

42 |

2 |

0 |

44 |

|

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

0 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

Department of Justice |

6 |

4 |

0 |

10 |

|

Department of Labor |

35 |

0 |

0 |

35 |

|

Department of State |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

Department of the Interior |

32 |

4 |

1,140 |

1,176 |

|

Department of the Treasury |

67 |

2 |

0 |

69 |

|

Department of Transportation |

0 |

7 |

0 |

7 |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

423 |

32 |

174 |

629 |

|

Executive Office of the President |

4 |

8 |

0 |

12 |

|

General Services Administration |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Institute of Museum and Library Services |

18 |

0 |

0 |

18 |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

0 |

3 |

626 |

629 |

|

National Archives and Records Administration |

10 |

1 |

0 |

11 |

|

National Science Foundation |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

National Transportation Safety Board |

0 |

7 |

0 |

7 |

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Office of Personnel Management |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Railroad Retirement Board |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Small Business Administration |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Social Security Administration |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

US Consumer Product Safety Commission |

0 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|

TOTAL |

728 |

353 |

110,077 |

111,158 |

Table 2: Datasets and Tools by Agency/Organization (as of 11/18/09)

2.4. Who Makes Data.gov Work: Key Partnerships

Agency Roles and Responsibilities

Agencies, via their data stewards, are the key partners responsible for populating Data.gov with high value, authoritative data. Agency Chief Information Officers (CIOs) have appointed Points of Contact (POC) to coordinate both within their agency and between their agency and the Data.gov Program Management Office (PMO). The POCs have direct support from the Data.gov PMO office as appropriate so the POCs can focus on serving their own data stewards. The data stewards are the focus for developing metadata, ensuring quality of their own data, and evolving high quality data oriented tools for the public to use. The POCs are key points of coordination as they help form a bridge between the many agency data stewards and the Data.gov PMO.

Agencies’ functional roles related to Data.gov include:

· Agency administrators, in support of enterprise transparency, should direct their program offices and CIO to jointly coordinate and support Data.gov requirements.

· Agencies are encouraged to vet Data.gov requirements through a Data Stewards’ Advisory Group or equivalent internal organization, whose participants would represent each of the agency’s program areas. This will have the effect of empowering individuals agency-wide who are most familiar with potential datasets that could be made ready for public dissemination.

· Agency program offices are the source of the data that are posted to Data.gov.

o Program offices are responsible for determining which data and tools are suitable to be posted on Data.gov, being mindful of the significance of exposing data through Data.gov in terms of the authoritative and high quality nature of data being included in a high profile Presidential Initiative.

o Program offices retain the right and responsibility for managing their own data and providing adequate technical documentation. This role tends to be carried out by program offices within the context of their particular missions. The term ‘data steward’ is used to refer to the agency staff that is directly responsible for managing a particular dataset.

· Agency program offices are responsible for ensuring that the data stewards for a particular data asset complete the required metadata for each dataset or tool to be publicized via Data.gov.

· Agency program offices should facilitate Data.gov POCs and CIO efforts to understand and catalog data assets, as indicated below.

· Agency program offices, in conjunction with Data.gov POCs and CIOs, are responsible for ensuring that their data assets are consistent with their statutory responsibilities within the context of information dissemination, including those related to information quality, security, accessibility, privacy, and confidentiality.

· Agency CIOs, in conjunction with program partners, are responsible for cataloging[8] and understanding their data assets, establishing authoritative sources, and ensuring the high quality of data. Agencies are encouraged to engage their enterprise architecture programs to formally catalog their data assets, determine which sources are authoritative, and evaluate adherence to information quality guidelines. Agencies are encouraged to leverage the Federal Data Reference Model which provides agencies with assistance to:

o Identify how information and data are created, maintained, accessed, and used;

o Define agency data and describe relationships among mission and program performance and information resources to improve the efficiency of mission performance.

o Define data and describe relationships among data elements used in the agency’s information systems and related information systems of other agencies, state and local governments, and the private sector[9].

· Agency CIOs and program offices have the responsibility of ensuring that authoritative data sources are made available in formats that are platform independent and machine readable. Agency enterprise architecture programs should promote the publication of web services, linked open data, and general machine readable formats such as XML

· Agency CIOs have the responsibility for assigning an overall Data.gov “point of contact” for their agency (POC). The agency’s Data.gov point of contact (POC) is responsible for ensuring that the requested documentation accompanies all datasets posted to Data.gov.

o The POC is responsible for training data stewards as to the importance of the metadata template that accompanies a Data.gov submission as well as how to complete this template.

o The data steward has the responsibility for documenting the agency’s data using the Data.gov metadata template and the POC should help coordinate the exposure of this metadata to Data.gov in one of the several ways detailed in this Concept of Operations document.

o The data steward is responsible for ensuring that the data is compliant with information quality guidelines and other applicable information dissemination requirements, that the corresponding metadata are compliant with the Data.gov requirements and are complete, and that the data are available online through the agency’s website.

·

The

POC is responsible for understanding Data.gov processes, Data.gov metadata

requirements, and compliance requirements for coordinating data submissions for

the agency. The Data.gov POC role is expected to evolve as each agency’s

dissemination processes mature and the Data Management System improves (as

discussed in the next section). Initially, the role and responsibilities of

these POCs are as follows:

The

POC is responsible for understanding Data.gov processes, Data.gov metadata

requirements, and compliance requirements for coordinating data submissions for

the agency. The Data.gov POC role is expected to evolve as each agency’s

dissemination processes mature and the Data Management System improves (as

discussed in the next section). Initially, the role and responsibilities of

these POCs are as follows:

o POCs are responsible for coordinating an internal (agency) process for working with the program offices to ensure the identification and evaluation of data for inclusion in Data.gov. Such a process must include: a) screening for security, privacy, accessibility, confidentiality, and other risks and sensitivities; b) adherence to the agency’s Information Quality Guidelines; c) appropriate certification and accreditation (C&A); and d) signoff by the program office responsible for the data.

o The POC is also responsible for facilitating feedback to Data.gov from the data stewards regarding improvements to the metadata requirements, including recommendations that generate taxonomies to facilitate interoperability.

· Critical success factors for POCs include:

o Establishing, populating, and moving agency data and tools through a “pipeline” culminating in inclusion in Data.gov.

o As Data.gov matures, bring back to their agency, program office, and data stewards concrete feedback on the value generated and feedback garnered via Data.gov.

o Serving as a conduit for agency participation in the evolution and successful realization of target outcomes for Data.gov.

Senior Advisory Group

The Executive branch hosts many interagency efforts that focus on missions associated with data policy, information management, and enhancing the dissemination of digital data. Representatives of many of these formal communities of interest have been recruited to serve on a council of senior advisors to Data.gov, including:

· The Chief Information Officers’ (CIO) Council, which includes the CIOs from all Chief Financial Officer-Act departments and agencies.

· The Interagency Council on Statistical Policy (ICSP), which includes representation from 14 principal Federal statistical agencies;

· The Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC), an interagency committee that promotes the coordinated development, use, sharing, and dissemination of geospatial data on a national basis;

· The Commerce, Energy, NASA, and Defense Information Managers Group (CENDI), an interagency working group of senior scientific and technical information (STI) managers from 13 Federal agencies:

· The Interagency Working Group on Digital Data (IWGDD), coordinated by the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP);

· The Networking and Information Technology Research and Development (NITRD) Program, the Nation's primary source of federally funded revolutionary breakthroughs in advanced information technologies such as computing, networking, and software.

Their input serves both to ensure alignment across the Executive branch with respect to modernizing information dissemination and to motivate their colleagues in their home agencies to become more active in making their data assets available to Data.gov. Specifics on the Advisory Group include:

· The Advisory Group is designed to be a vehicle for cross-government fertilization with respect to information policy and transparency opportunities raised by the Data.gov initiative as well as a mechanism for mobilizing support for and implementing the transformational goals of Data.gov. Furthermore, the Senior Advisory Group helps the Data.gov team understand and establish models, frameworks, and technology support for performance measurement and management around information quality, dissemination, and transparency.

· The Advisory Group is one of several vehicles that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) uses to obtain advice on the direction of Data.gov. OMB also receives advice from the Project Management Office at GSA, the CIO-appointed agency POCs, representatives of related websites described in Section 4, as well as from technology and information policy leaders outside the government, and Data.gov users.

· The Advisory Group is wholly comprised of senior level Executive Branch (government) employees. Participants are representatives of existing, formally chartered Executive Branch communities of interest around information policy and transparency. Additional communities of interest may be nominated for potential representation on the Council; OMB will determine the goodness of fit, and offer invitations as appropriate.

· In addition to representing the perspective of their Federal community of interest, Advisory Group participants will be asked to speak from the perspective of agency data stewards.

· The Advisory Group is not a decision making or voting body, and consensus will not be sought.

· The Advisory Group is co-led by OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs and OMB’s Office of E-government and Information Technology.

The Advisory Group:

· Encourages the development and implementation of a unified vision for achieving data interoperability and other efforts to modernize Executive Branch data dissemination and sharing.

· Provides OMB with a forum for working interactively with senior program executives, agency data stewards, and others responsible for the generation and dissemination of data accessible through Data.gov.

· Provides feedback to OMB on the potential impact of Data.gov proposals on agency and interagency data generation and dissemination programs.

Subject Matter Expert Technical Working Groups

Data.gov will harness the interests and expertise of staff across the Government when it stands up technical working groups designed to develop approaches to modernizing and streamlining data formats and structures to allow linking, tagging, and crawling. For instance, the Data.gov team will draw on expertise from across the Government to provide advice regarding the best approaches to publishing metadata that facilitate encoding meaning into datasets in such a way that they are directly interpretable by computers and that strengthen the interoperability of Federal datasets.

Federal Communities of Interest/Information Portals

Other interagency efforts, such as Science.gov and Fedstats.gov, are focused on serving distinct user communities and to make information easier to find and more useful for those communities. These Federal communities of interest often disseminate their data through information portals. Increasingly, these sites will have the opportunity to mimic the design patterns of Data.gov including the metadata template, catalog capabilities, and end user search and feedback capabilities.

Federal communities of interest that offer these information portals to the public are encouraged to first standardize a metadata taxonomy or syntax to be shared with Data.gov, and then communicate any changes to it as the community evolves the standard. These communities of interest are encouraged to expose corresponding data either as downloadable data, query points, or tools. In this way, the information portals provided by these Federal communities of interest will become more standardized in how their data is maintained and shared, and these information portals will become networked to Data.gov to allow for maximum visibility, discoverability, understanding and usefulness of the data.

State, Local, and Tribal Involvement

Although Data.gov does not catalog state, local, or tribal datasets, there is a shared benefit of cross-promoting efforts to catalog and make non-Federal data assets more transparent. State, local, and tribal governments are encouraged to leverage the thoughts, ideas, and patterns used by Data.gov to develop their own Data.gov style solutions. State, local, and tribal governments are also encouraged to inform the Data.gov team of their own implementations so that Data.gov can link to those specific sites.

Furthermore, state, local, and tribal governments are encouraged to innovate new and interesting ways of cataloging, presenting, searching, and visualizing their data. State, local, and tribal governments are also encouraged to find more interactive and elegant ways of interacting directly with the public. As innovations are implemented, non-Federal governments are encouraged to share these breakthroughs with the Data.gov team for potential use on Data.gov.

International Standardization Organizations

Key stakeholders in the development and continual improvement of Data.gov will include the relevant bodies that set international standards related to Data.gov’s processes, including the World Wide Web Consortium, International Standardization Organization, National Institute of Standards and Technology, or the actual standards themselves, such as Dublin Core.[10] As Data.gov evolves, it may be necessary to build upon or add to these standards, and even make recommendations to these organizations to update their standards. Data.gov will look to the expert domain communities within the Federal government to work with these organizations and recommend adjustments to Data.gov’s processes and metadata requirements.

3. Future Conceptual Solution Architecture

The current state physical architecture for Data.gov consists of a website and a relational database that serves as the metadata catalog containing the site’s content. The evolution of the physical architecture will be based on the conceptual architecture that is depicted in this document. The conceptual architecture has been developed based on feedback from the user community, feedback from the data producing Federal agencies, and overall alignment with Data.gov’s strategic intent and core design principles outlined in section 1 of this document.

The feedback on the current Data.gov architecture has been fairly uniform in that:

· Federal agencies that produce data want an easier way to make their data available on Data.gov

· End users of Data.gov want easier ways to use the metadata from Data.gov and the actual agency data represented on Data.gov

The conceptual architecture for Data.gov has been evolved in response to this feedback. Like any architecture effort, there are many ways to architect the solution and still satisfy most areas of feedback. Several architectural alternatives were established and reviewed in the context of the core design principles outlined in Chapter 1 of this document: (1) providing a solution that focuses access to data and facilitating third-party application and website developers, (2) leaving control of data dissemination to the programs that produce the data, (3) providing mechanisms to rapidly disseminate data, (4) providing mechanisms to receive and act on feedback, (5) leveraging common solutions,(6) implementing a component or module based solution, and (7) implementing a solution that aids in developing and extending best practices.

This vision can be fulfilled through the delivery of several technical components, including six core modules and four data infrastructure tools that are described in further detail in section 3. The core modules will include (1) the website, (2) the Data Management System (DMS), (3) the metadata catalog, (4) a performance tracking and analysis engine, (5) an audit tool, and (6) a hosting service. The initial data infrastructure tools include collaboration, feedback, agency and site performance dashboards, and search related tools. It is expected that the Data.gov team will focus on building or acquiring the core modules and partner with others on the development and operations of the data infrastructure tools. The core modules and data infrastructure are to be based on open standards and aligned with web trends and patterns. Further, the conceptual architecture supports innovation by the Data.gov team and others to increase the number, scope, and operating or business models for data infrastructure tools.

The modular architecture, and the ability to leverage other governmental and other entities with respect to data infrastructure tools, enables the Data.gov team to iteratively build out the solution in line with allocated budgetary resources while still accelerating realization of the end-to-end vision.

3.1. Security, Privacy and Personally Identifiable Information

The Administration is committed to ensuring that Data.gov does not compromise privacy or confidentiality. Specifically, agencies that make their data available online must ensure that the data does not include personally identifiable information or in any way compromise law and policy. In addition, the Data.gov team will enhance and extend working groups under the Senior Advisory Group to learn from third party use of Federal data with an eye towards better understanding the effect of new mash-ups and applications on intentionally and unintentionally unmasking sensitive personally identifiable information and/or creating security-related issues. These working groups will recommend enhancements to policy and guidance as needed.

Privacy considerations extend beyond the data itself to include the way that Data.gov measures performance and gathers feedback from the site. All feedback provided through Data.gov is anonymous with no tracking or identifier information captured. Furthermore, performance statistics will be gathered as specified within this document. Performance measures will be specifically targeted at macro use statistics without any identification of specific uses of specific data by individuals or groups.

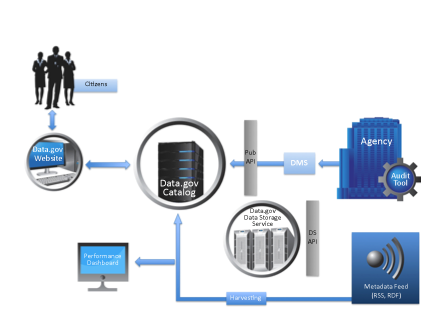

3.2. Core Modules

As depicted in the following visual, Data.gov’s future architecture will include six core modules: (1) the website, (2) the DMS, (3) the metadata catalog, (4) a performance tracking and analysis engine, (5) an audit tool, and (6) a hosting service. The architecture will also utilize at least four data infrastructure tools: collaboration, feedback, agency and site performance dashboards, and search related tools. The modules and tools will be made more accessible through a collection of application programming interfaces (API) that expose metadata and data. Together, these modules, tools, and APIs will allow Data.gov to adapt to its customer base as needed. Note that many of the capabilities outlined in section 2, such as the Dataset Management System, are currently in use. Where this is the case they will be enhanced and extended. In other cases, for example the data infrastructure tools, the Data.gov team will partner with others to deliver the capability.

Figure 8: Conceptual Architecture Overview Diagram

Module 1 – The Site

All citizens, technically inclined or not, can access the Data.gov website to discover structured data, otherwise known as data sets, published by the federal government and download them to their local computer. To serve up these data sets, the Data.gov website accesses a catalog of records with one record representing each data set published to it.

Data.gov visualization services could be delivered through the site and could include analytics, graphics, charting, and other ways of using the data. In many cases enhanced visualizations will be delivered by the Data.gov team or others as data infrastructure tools, built on top of published APIs. These enhanced visualizations or other uses will in some cases be accessed via the Data.gov site and in others via external web sites.

Another enhanced feature of Data.gov could allow customers to receive alerts on the availability of new data sets in a subject area in which they are interested. A variation of this would be alerts to developers related to changes or updates to data sets they use to power their applications. Alerting and notification as a feature could be implemented via a data infrastructure tool, or via specific features added into core modules, or both. This seems an area where Data.gov should implement a basic capability and invite experimentation and innovation to identify opportunities for greater added value – data domain specific, in general, or in some unforeseen manner.

Figure 9: DMS Screenshot

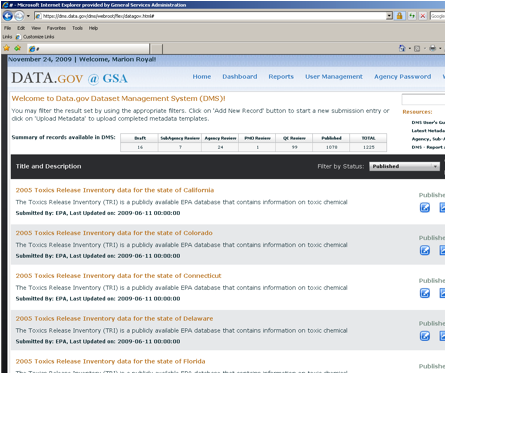

Module 2 – The Dataset Management System

The Dataset Management System (DMS) was recently unveiled to facilitate agencies’ efforts to organize and maintain their Data.gov submissions via a web-based user interface. The Data.gov DMS provides agencies a self-service process for publishing datasets into the Data.gov catalog. The DMS is the approach of choice if an agency does not have its own metadata repository and does not have the resources to leverage the Data.gov metadata API or harvesting approaches.

The DMS allows the originators to submit new datasets and review the status of previously submitted datasets. New datasets can be submitted either one dataset or multiple datasets at a time. Once a dataset suggestion has been added to the DMS, its status can be tracked through the submission lifecycle. Agency POCs can access the DMS to view the entire published catalog, all published datasets and tools submitted by their agency, and a dashboard of all pending submissions. The DMS could, in the future, also disclose to the POCs compliance issues that are not being met by the agency and its data stewards.

Module 3 – The Metadata Catalog

The Data.gov metadata catalog will evolve into a shared metadata storage service that allows agencies to utilize a metadata repository that is centralized in a Data.gov controlled host, and use it for their own needs. Agencies that do not have metadata repositories of their own will be able to leverage Data.gov’s shared metadata repository as a service. So that agencies can leverage the shared metadata repository as an enterprise service, agencies will be able to flag which of their metadata they choose to share with the public via Data.gov versus those stored in the service but not exposed via Data.gov. Additionally, agencies will be able to designate whether their data contains personally identifiable data and whether the data adheres to information quality requirements.

Figure 10 depicts the key components of a catalog record. It is important to understand that while these various components are drawn in separate boxes, they are actually all part of a single catalog record.

Figure 10: Catalog Record Architecture

The four parts of a robust catalog record are:

· Catalog record header – this part holds both administrative book-keeping parts of the overall record and all data needed to manage the target data resource. To manage a target data resource, this part will keep track of ratings, comments and metrics about the resource.

· Data resource part – a data resource is the target data referred to by the catalog record. A data resource could be a dataset, result set or any new type of structured data pointed to by a catalog record.

· Data resource domain part – a data resource belongs to a domain or area of knowledge. The domain of a data resource has two basic parts: resource coverage and resource context. Resource coverage is a description about what the resource “covers”. Resource context is metadata about the environment that produced the data including the production process.

· Related resources part – a structured data resource may have one or more resources related to it. For example, structured data may have images, web pages or other unstructured data (like policy documents) related to it. Additionally, as evidenced on the current site, a dataset may have tools related to it or tools that help visualize or manipulate the data.

Module 4 – Performance Tracking and Analysis Engine

Data.gov will include a performance tracking and analysis engine that will store Data.gov and wider Federal information on data dissemination performance. Data.gov related measures will be combined with Federal-wide data dissemination measures to gain a better understanding of overall Federal data dissemination. Agencies will supply measures to Data.gov and the total set of performance and measurement data will be made available to the public. A discussion of performance measures is in sections: “Measuring Success” and “Appendix A – Detailed Metrics for Measuring Success”.

Module 5 – Audit Tool

Over time, any organization can find that data have been published and exist in the public domain without active management or visibility inside of the organization. The Data.gov team may provide the expertise to assist agencies with identifying previously published data to assist those agencies in their own processes for data management and potential publication to Data.gov. The Data.gov team is considering deploying a search agent to scan Federal government domains in order to provide data that will assist agencies in evaluating their data management practices and accelerate integration of already public data resources into Data.gov.

The audit tool will prioritize delivery for a basic capability focused on identifying and characterizing already public data assets in a useful manner for agency POCs. It would scan through Federal domains and formulate an index of potential datasets and build reports to deliver to agencies. Associated reporting would serve to provide some basis for the total population of data, provide intelligence to agencies on their potential data assets, and serve to assist the data steward community with an assessment of what is currently exposed to the public.

This is not intended to automatically populate Data.gov, but rather to assist agencies with their own data inventory, management, and publication processes. The result should be better, more granular agency plans to integrate their already public data sets into Data.gov; more efficient and lower cost data management and dissemination activities through leveraging reported data to jump start and validate data inventories; enhanced ability to develop a proactive understanding of agency compliance with information dissemination and related policy. Most importantly, through continuous measurement the audit tool provides timely and actionable management data to agencies and makes their progress with integration into Data.gov transparent.

Module 6 – Shared Hosting Services

Data.gov will implement a shared data storage service for use by agencies. This service will be accessible via APIs and will provide agencies with a cost effective mechanism for storing data that will be made available to the public. The data stored within the service will be made available via feeds and APIs so that the application development community can receive direct enablement from Data.gov.

Providing data in the right format is as critical as providing the data themselves. For instance, the shared hosting service could be used to provide data using query points such as RESTful web services, web queries, application programming interfaces, or bulk downloads. Data can be made more useful through these services and by extending the metadata template to include data-type specific or domain-specific elements in addition to the core ‘fitness for use’ type metadata currently in the Data.gov metadata template. Agency use of query points drives value in some instances. For example, agencies using query points would be able to directly measure “run-time” use of their data as opposed to just recording instances of data downloads. Also, given agency control over the query point, agencies would be able to better support access to most the current and correct versions of data resources as well as more clearly understand downstream use and value creation resulting from their data resources.

Data storage and publishing (end user access) would be subject to metering of some sort, to be determined. Given the operational aspect of this module and the need to scale based on volume and end user usage of data, the Data.gov team will look to fully align on the Federal Cloud Computing Initiative and leverage its managed service focus for this module. The core value proposition to agencies for using the shared hosting service is integration with the other modules, as well as alignment with the cloud initiative, which should reduce total costs and enable more efficient and effective realization of the full Data.gov value proposition.

3.3. The Data.gov APIs

Developers will interact with Data.gov through multiple Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), as shown below in Figure 11. The APIs will give programmatic access to the Data.gov catalog entries and the data within the shared data storage service. These APIs are a near-term objective and are expected to be developed over the next six months.

Specifically, the APIs will be both inbound and outbound. Inbound APIs will allow developers from within the Federal government to submit data or tools to the metadata catalog and submit actual data to the shared data storage service. These inbound APIs will be the most automated way, in the near term, to submit data to Data.gov.

Outbound APIs will allow developers to leverage the data from the shared data service and the Data.gov metadata catalog to develop their solutions. Developers can build their own websites that leverage the Data.gov metadata catalog or can develop their applications using data from the shared data storage services. In these instances of developers leveraging the outbound APIs, the developers will be provided a means to submit usage statistics for their own applications and websites, as well as appropriate feedback, to help the government understand the overall usage and opportunities to improve the data being accessed via Data.gov. Additionally, the usage of the APIs will be metered and developers accessing those APIs will be required to register their use. Indeed, the metering will open opportunities for third-party innovation and business models around un-metered, fee-for service, third-party hosting and publication.

Figure 11: Developer Architecture

As shown in the diagram above, there are three APIs developers use to access specific parts of the Data.gov architecture. The main API, called the DEV or developer API, provides read access to all records in the Data.gov catalog. This includes all components of a catalog record as discussed in the content architecture section below. For searching for datasets and other related data (like unstructured data) the developer can use the search API which will be developed to search across both Data.gov and USAsearch.gov. For accessing datasets stored in the Data.gov storage service, the developer will be able to use the data storage, or DS, API to retrieve them.

3.4. Data Infrastructure Tools

The architecture for Data.gov includes data infrastructure tools that will enhance the Data.gov experience. Many of these data infrastructure tools will be developed not by Data.gov but by the expert communities that are most appropriate. For instance, the search data infrastructure tool will come from the work related to USAsearch.gov. The Data.gov architecture includes four data infrastructure tools as detailed below.

Data Infrastructure Tool 1 – Collaboration

Collaboration related tools will initiate and enable inter-agency communication as mission owners explore and find other mission owners with similar goals and areas of responsibility. These tools will be built by agencies and to their own functional and business specifications. They will, however, have to adhere to Data.gov’s technical specifications so they may be properly hosted (or accessible from) and utilized on the site.

Data Infrastructure Tool 2 – Feedback

Data.gov will be able to accommodate a variety of feedback tools as they are developed either internal to the government or by third parties. The feedback tools will allow the general public to engage more efficiently with the Federal government around Federal data sets and the tools can be re-used across Federal websites.

Data Infrastructure Tool 3 – Search

Since structured data, like data sets and query results (from query points, discussed previously), can be related to unstructured documents (like web pages indexed by USAsearch.gov), the Data.gov and USAsearch.gov teams are collaborating on an integrated search API and integrated search box widget, as depicted in Figure 12, that can federate search across both sites and return both structured and unstructured results.

Figure 12: Search Integration Architecture

As depicted in Figure 12, a single integrated search widget can be shared across both the Data.gov and USAsearch.gov websites. This single search widget will use the same integrated search API that will search across both the Data.gov and USAsearch index[11] (it could eventually be federated across other sites).

The utilization of USAsearch will provide an economy of scale that would not otherwise be achieved had the project team gone about developing its own search capability internally. The user interface (UI) of the search page could look similar to the following figures:

Figure 13 : Notional Data.gov Search Page User Interface

As indicated by the notional screenshots, Data.gov’s search page will display to each user the top queries by volume, top queries by trend (rate of change), and a keyword or tag cloud on the right. Additionally, users will have the ability to browse through each community of interest’s specific taxonomy.

In the near term, browsing Data.gov catalog holdings will be improved by the Data.gov technical working groups crafting a taxonomy (a hierarchical structure of topics) that allows users to drill-down by topic area. Data.gov’s search capability will be improved by adding an advanced search feature, end-user tagging (known as a folksonomy) of datasets and the ability to “search inside” datasets for keywords. The advanced search feature will expand the number of data types that can be selected for search to include XML, RDF and all other formats contained in the catalog.

Figure 14: Notional Data.gov Search Results User Interface

Other advanced discovery mechanisms including geographic searching are being targeted for future releases. The Data.gov team will work with the FGDC to support their development of this capability for integration into the Data.gov solution. Geospatial search would allow an end-user to draw a bounding box on a map, constrain the results by time or topic areas and then query the Data.gov catalog and visually return the hits that fall into that area. An example of this would be to display icons for any datasets on brownfields in a specific geographic area. In addition to Data.gov implementing this functionality directly the team will explore expanding the APIs as appropriate to include geospatial search by external websites. Figure 14 below is a notional illustration of the concept.

Data Infrastructure Tool 4 – Agency and Site Performance Dashboards

The agency and site performance dashboards will display the relevant metrics that are collected by the performance and analysis engine. As previously discussed, each agency will collect and share performance metric information with Data.gov through an automated process. This process will standardize the incoming performance data, and then load the data into a viewable dashboard environment that will be displayed to the public, Data.gov personnel, and agency personnel. The public’s performance dashboard will have limited access to the performance metrics. The performance data will be re-usable across Federal websites as well as by the public.

Figure 15: Notional Data.gov Geospatial Search Tool

3.5. Agency Publishing Mechanisms

An agency will have three mechanisms to publish metadata records to Data.gov. These three mechanisms are:

1. The Dataset Management System – this is a protected website only accessible by authorized users as described previously. This website will enable agencies to publish metadata records to the Data.gov catalog in accordance with the agency’s dissemination process.

2. A Publisher API – an application programming interface that will allow an agency the ability to programmatically submit one or more records into the Data.gov catalog.

3. A Metadata Feed – if an agency desires to control publishing of metadata records on their own websites, the Data.gov PMO harvesting service will read the metadata feed and publish the records to the Data.gov catalog. The metadata feed will be a file in a standard feed format like Really Simple Syndication (RSS) or the Atom Syndication format.

Figure 16: Publishing Architecture

3.6. Incorporating the Semantic Web

OMB Memorandum M-06-02 released on December 16, 2005, stated “when interchanging data among specific identifiable groups or disseminating significant information dissemination products, advance preparation, such as using formal information models, may be necessary to ensure effective interchange or dissemination”. OMB Memorandum M-06-02 further noted that “formal information models” would “unambiguously describe information or data for the purpose of enabling precise exchange between systems”.

A good example of this is OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affair’s development, support, and use of formal statistical policy standards[12] like the standards for data on Race and Ethnicity, Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA), and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Agencies can enable cross-domain correlation between datasets by tagging datasets or fields in datasets as belonging to standard categories of such data standards. For example, let’s say a web-savvy developer wants to create a mashup that visualizes and ranks various industries on revenue per employee. If one agency has published data on a designated industry’s revenue and another agency has published data on its employment, then these records could be correlated if both datasets are categorized via the standard NAICS codes to produce revenue per employee for the given industry. Through reuse of these semantically harmonized and uniquely identified categories across domains, the data from multiple sources can be appropriately merged and new insights achieved.